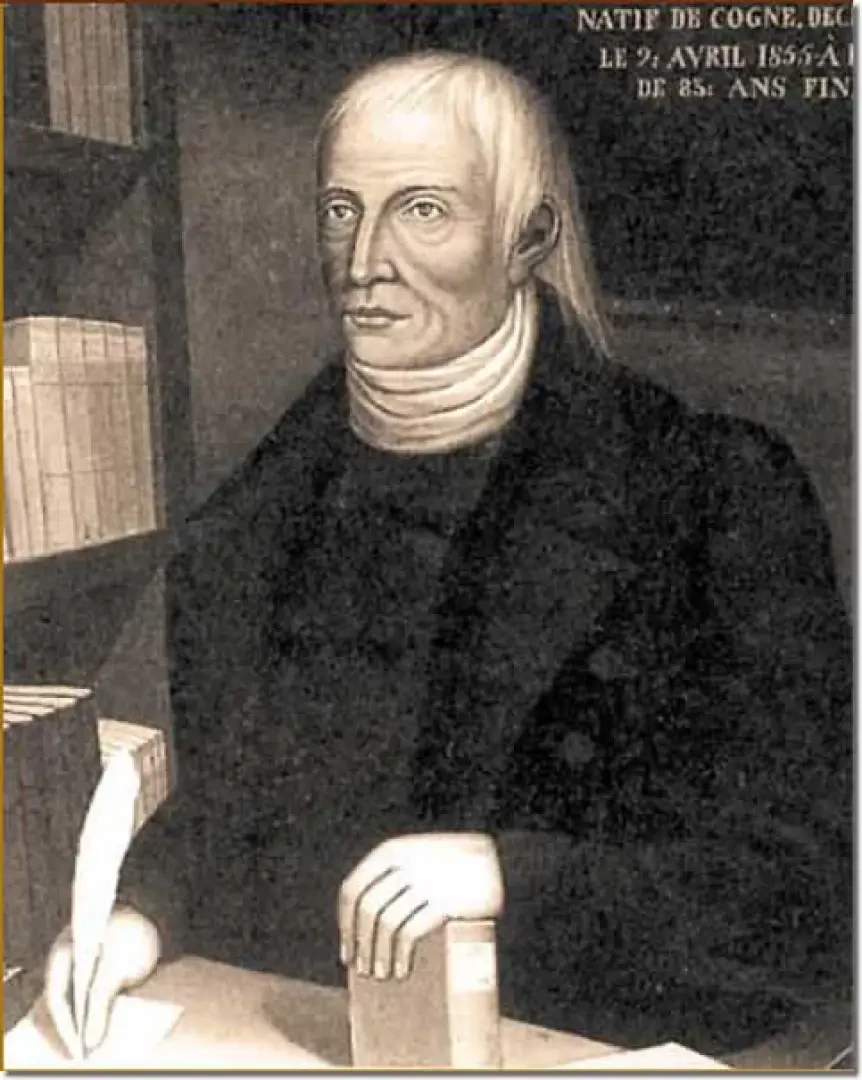

Dr Grappein', as he went down in history, was born in Cogne and, as was often the case at the time, especially in Valle d'Aosta, was directed towards ecclesiastical studies. In this case, however, non-vocation prevailed and he turned to the study of medicine, graduating on 21 May 1804. From then on, Dr Grappein practised the profession of doctor in Cogne until his death, often free of charge to help the poorer strata of the population.

Dr Grappein', as he went down in history, was born in Cogne and, as was often the case at the time, especially in Valle d'Aosta, was directed towards ecclesiastical studies. In this case, however, non-vocation prevailed and he turned to the study of medicine, graduating on 21 May 1804. From then on, Dr Grappein practised the profession of doctor in Cogne until his death, often free of charge to help the poorer strata of the population.

But the memory that is still preserved of him is linked to his activity as a public administrator and in particular to the management of the iron mines. He was in fact a firm believer in the principle that foreign entrepreneurs did not benefit the community, looking first and foremost for their personal gain. He thus organised a communal exploitation of the deposits, using only local labour and distributing the profits equally to the entire population of the village, including children. Needless to say, this attracted him the hatred of the bourgeois and industrial classes, from which he defended himself through various furiously polemical writings that have come down to us.

Among his further insights into social development was the need for mass education as a remedy against poverty and lawlessness: education should have been public, free (in the sense of non-singular) and practised in small classes (contrary to what was the case at the time) so that children could be better looked after; finally, teachers should have been paid a salary commensurate with their delicate task (something else that contrasted with the reality of the situation).

He was mayor of the town for many years and in this capacity he was a proponent of an elective local administration, if not by universal suffrage, at least representing the will of every head of a family: at the time a strict census principle was in force. Finally, public offices were to be of short duration.

He specifically fought against the prevailing misery and identified its causes in the poverty of the land, unsuitable for agriculture, in the compulsory conscription that robbed the best labour forces (and often the very lives of conscripts) and in the presence of taverns as the only possible recreation, with its inevitable corollary of widespread alcoholism. Work for all therefore appeared to him as the main source of social redemption and this is why he refused to entrust municipal 'contracts' to outside companies, but always used specially recruited and paid fellow citizens. Among these works was his attempt to improve direct communications with the neighbouring Piedmontese side, in order to boost trade and find cheaper goods. He also built five irrigation canals to support agriculture, even though he was an advocate of abandoning less productive land and turning it into pastureland, in virtue of a more favourable work-rents ratio, (but on this point he clashed with the obstinacy of his fellow villagers).